Welcome to the third week of the “Beginnings are Hard” series. In these posts, I analyze the first 500 words (or so) of award-winning or bestselling novels to see how they work.

For an in-depth introduction, an explanation of my methodology, and a look at Ted Chiang’s Story of Your Life, click here.

Interested in hiring me as a developmental editor, book marketing copywriter, or need a fresh pair of eyes on your first chapter? Check out the Archetypist “Services” page for more info.

The Crash Course Intro:

I first learned about this diagnostic at a workshop put on by Kurestin Armada, a literary agent. This simple highlighting system can be used to analyze what work your words are doing, and what areas of your beginning may be lacking. Not every sentence of your manuscript will be highlighted, but if there’s more than 10-15% of un-highlighted words, there’s probably work to be done.

The exercise:

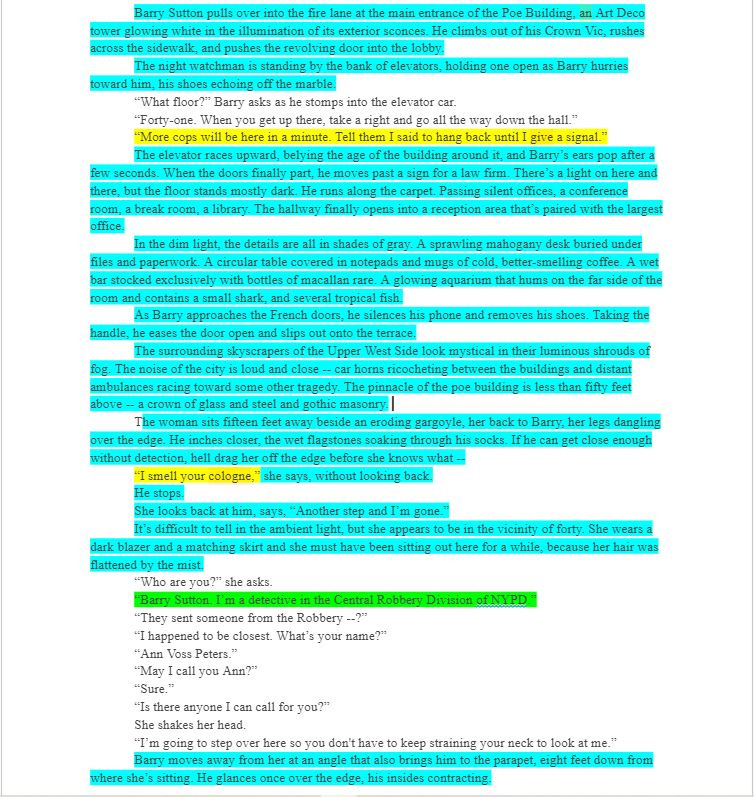

Take the first 2 pages (500 words) of your novel and print them out. Make two copies. Then get 4 different colored highlighters and mark the following:

Character is revealed in Green

Plot/Conflict is revealed in Red

Setting/Description in Blue

Two or more of the previous 3 happening at once: Gold (or the gold standard).

This exercise is meant to be done by an uninformed reader, as if your manuscript just came across an editor’s desk that wouldn’t know you from Adam. That’s why, when you’re analyzing your own work, it’s important to switch with a critique partner or two. You already know how your story ends. They don’t. If there are discrepancies between your highlighter colors, that tells you that you’re relying on the rest of your story to carry your beginning. I find that, as I’ve gone back after reading these novels a second time, I’m more liberal with my yellow highlighter because I can see the shape of the story reflected in the first pages.

The un-highlighted excerpt is pasted below, followed be a screengrab of my highlighting system. See you on the other side!

Recursion

by: Blake Crouch

Barry Sutton pulls over into the fire lane at the main entrance of the Poe Building, an Art Deco tower glowing white in the illumination of its exterior sconces. He climbs out of his Crown Vic, rushes across the sidewalk, and pushes the revolving door into the lobby.

The night watchman is standing by the bank of elevators, holding one open as Barry hurries toward him, his shoes echoing off the marble.

“What floor?” Barry asks as he stomps into the elevator car.

“Forty-one. When you get up there, take a right and go all the way down the hall.”

“More cops will be here in a minute. Tell them I said to hang back until I give a signal.”

The elevator races upward, belying the age of the building around it, and Barry’s ears pop after a few seconds. When the doors finally part, he moves past a sign for a law firm. There’s a light on here and there, but the floor stands mostly dark. He runs along the carpet. Passing silent offices, a conference room, a break room, a library. The hallway finally opens into a reception area that’s paired with the largest office.

In the dim light, the details are all in shades of gray. A sprawling mahogany desk buried under files and paperwork. A circular table covered in notepads and mugs of cold, better-smelling coffee. A wet bar stocked exclusively with bottles of macallan rare. A glowing aquarium that hums on the far side of the room and contains a small shark, and several tropical fish.

As Barry approaches the French doors, he silences his phone and removes his shoes. Taking the handle, he eases the door open and slips out onto the terrace.

The surrounding skyscrapers of the Upper West Side look mystical in their luminous shrouds of fog. The noise of the city is loud and close -- car horns ricocheting between the buildings and distant ambulances racing toward some other tragedy. The pinnacle of the poe building is less than fifty feet above -- a crown of glass and steel and gothic masonry.

The woman sits fifteen feet away beside an eroding gargoyle, her back to Barry, her legs dangling over the edge. He inches closer, the wet flagstones soaking through his socks. If he can get close enough without detection, hell drag her off the edge before she knows what --

“I smell your cologne,” she says, without looking back.

He stops.

She looks back at him, says, “Another step and I’m gone.”

It’s difficult to tell in the ambient light, but she appears to be in the vicinity of forty. She wears a dark blazer and a matching skirt and she must have been sitting out here for a while, because her hair was flattened by the mist.

“Who are you?” she asks.

“Barry Sutton. I’m a detective in the Central Robbery Division of NYPD.”

“They sent someone from the Robbery --?”

“I happened to be closest. What’s your name?”

“Ann Voss Peters.”

“May I call you Ann?”

“Sure.”

“Is there anyone I can call for you?”

She shakes her head.

“I’m going to step over here so you don't have to keep straining your neck to look at me.”

Barry moves away from her at an angle that also brings him to the parapet, eight feet down from where she’s sitting. He glances once over the edge, his insides contracting.

444/568 -- 78% -- Description

12/568 -- 2% -- Character

4/568 -- 0.007% gold standard

87/568 -- 15% uncategorized

The Analysis

Regular readers (as regular as one can be after only two other posts) will note that, in my introduction to this series, I referenced that if more than 10-15% of your first pages are listed as “uncategorized,” you might need to do some revisions. I’m giving this piece a pass, because most of the uncategorized words here are dialogue, which could be categorized as “character.” I, however, am not categorizing it as such for two reasons:

The dialogue in question progresses the scene, which is important, but it doesn’t “reveal the plot” or “reveal the character” in a profound way. It functions well within the scene, but taken on its own, it doesn’t do much heavy lifting in the way of hooking the reader.

I generally advise new writers against opening up their novel with dialogue, even if it’s dialogue that reveals character in the mind of the writer , because it’s not the character’s external voice that drives the novel, it’s their internal perspective.

This example is also a bit of an outlier because it’s so description-heavy. In fact, 78% of these words are just the character noting the accidents of the setting. This is a situation where the context / subtext is important. Generally, if you told me that out of your novel’s first 600 words, about 450 of them were description — and ONLY description, not a plot-description or character-description hybrid — I’d advise you to change it.

Here, however, it’s the unwritten subtext that provides the narrative motion and scene tension. Barry enters the scene with an objective and in motion. He immediately addresses the footman and tells him that more cops are on the way, giving us our first clue of what’s going on and a character-plot hybrid: there’s some sort of crisis, Barry is a cop, and there’s more on the way.

This method of opening your novel is actually more difficult than it seems. Starting with brisk action, while it may seem like a smart move at first, nearly always alienates the reader (like starting with a fight scene, for example). Action without stakes is boring, like tuning into a random sporting event. Here, the mystery of what’s coming next propels the scene. Why is Barry here? Why are more cops coming? Why is he noticing what he’s noticing? Why is this woman, who apparently is ready to jump to her death, so calm and collected?

All of this comes together to create a killer opening, despite the fact that all we know about Barry is that he is a police officer from robbery.

The last thing I’ll note here is that there is not one clue in nearly 600 words that this novel is a Sci-Fi thriller. I thought I was getting into a police procedural/hardboiled detective novel. Again, I’d advise new writers to at least tip the reader of that we’re in a sci-fi world within the first 500 words, especially first-time novelists looking to break into the industry. I suppose this book may get a pass because it’s pretty much our world/technology level, save for one big difference that’s revealed later. It’s not first contact or far future SF with a wild setting.

Overall, I’d rate this beginning as effective and engaging, but, as I said, I wouldn’t recommend imitating it for a writer looking to break into the industry for the first time. That said, the book did win the Goodreads Reader’s Choice Award and I tore through the rest of the novel in about 7 hours. I’d highly recommend reading the whole novel and even imitating its general structure.

Next week, we’ll look at Nettle & Bone by T. Kingfisher.