Beginnings are Hard: Series Introduction & Story of Your Life by Ted Chiang

An in-depth analysis of his first 500 words

Beginnings are hard. Really hard. So hard, in fact, that they’re probably the most changed, cut, or revised part of a novel. They’re hard because they have to accomplish multitudes: introduce the character, the setting, the main story problem, set genre expectations, give the reader an impression of the piece’s voice; telegraph to the reader that, yes, you’re a professional and no, this won’t be a waste of time. An engaging beginning encourages reader buy-in. It can convert that agent’s “Yeah, send me a 1-page synopsis and your first 10 pages,” request to “Ok, this looks like something I might be interested in. Send me the full manuscript.” Your beginning is your book’s pitch to anyone who picks it up in the bookstore or clicks on the LOOK INSIDE button on Amazon. It is your one chance to make a sale. So, in this series, we’re going to look at what makes a good beginning.

I’ve probably read more beginnings than most writers — more beginnings than most readers, even. Between studying English in undergrad, to studying Popular Fiction for graduate school, to reading slush for Flash Fiction Online, the Overcast, and Black Hare Press, to teaching undergraduate creative writing, to attending workshops and conventions, to taking on my own developmental editing clients, to putting on programs at my local library. I’ve read a certifiable buttload of beginnings. And that’s not even counting the novels that I read on a regular basis.

All that to say: I (and virtually all teachers and slush readers) usually know if a story is a good fit for the publication within the first page. About 80% of the time, however, I’m pressing the “reject” button within the first paragraph, or even within the first few sentences (in flash pieces) simply because the story had one of the following problems:

it had a cliché as its premise,

it wasted time focusing on seemingly unimportant details,

the writer did not have a good grasp of immersive, engaging writing,

it became apparent that the piece was not actually a story, but a scene painted beautifully with descriptive language but utterly lacking conflict.

this “not a story” critique constituted the bulk of my rejections that I sent to my team and eventually to the EIC for approval.

So, we’re going to learn how to self-diagnose our work so this doesn’t happen.

At Seton Hill’s In Your Write Mind convention back in 2017, I attended a workshop put on by Kurestin Armada, who, at the time, was a literary agent with P.S. Literary. She took us through a simple, diagnostic exercise that she used with her clients to analyze their beginnings , diagnose problems, and help them be more dynamic:

Take the first 2 pages (500 words) of your novel and print them out. Make two copies. Then get 4 different colored highlighters and mark the following:

Character is revealed in Green

Plot/Conflict is revealed in Red

Setting/Description in Blue

Two or more of the previous 3 happening at once: Gold (or the gold standard).

Switch with a critique partner. Give them the second, blank copy of your story and take each other’s stories through the same exercise. Then, compare notes.

NOTE: It’s important to remember that each of these elements of story have their place. They can and do appear in any order on the page (though there is also conventional wisdom regarding which to place first for reader retention). Also, not everything will be highlighted, and that’s OK, but if you’re finding that you have more than, say, 10%-15% of your first pages un-highlighted, figure out why that is. Odds are, there’s work to be done.

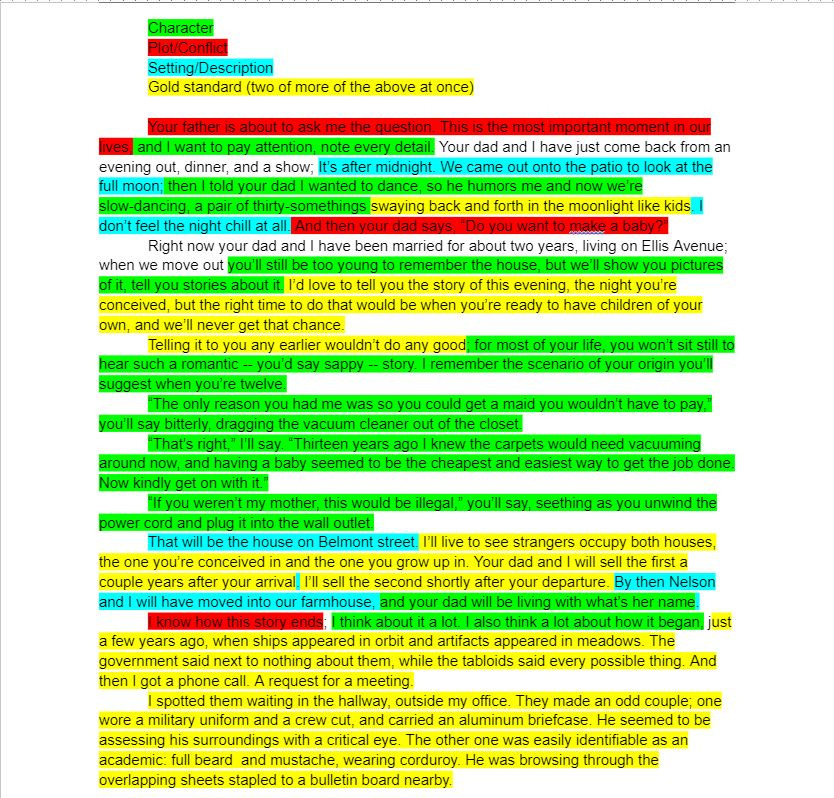

Below, I’ve included an example from Ted Chiang’s novella Story of Your Life. First, you’ll see the story as it appears on the page. Next, you’ll see an image of the highlighting exercise because, apparently, Substack doesn’t allow highlighting.

See you on the other side:

Story of Your Life

By: Ted Chiang

Your father is about to ask me the question. This is the most important moment in our lives, and I want to pay attention, note every detail. Your dad and I have just come back from an evening out, dinner, and a show; It’s after midnight. We came out onto the patio to look at the full moon; then I told your dad I wanted to dance, so he humors me and now we’re slow-dancing, a pair of thirty-somethings swaying back and forth in the moonlight like kids. I don’t feel the night chill at all. And then your dad says, “do you want to make a baby?”

Right now your dad and I have been married for about two years, living on Ellis Avenue; when we move out you’ll still be too young to remember the house, but we’ll show you pictures of it, tell you stories about it. I’d love to tell you the story of this evening, the night you’re conceived, but the right time to do that would be when you’re ready to have children of your own, and we’ll never get that chance.

Telling it to you any earlier wouldn’t do any good; for most of your life, you won’t sit still to hear such a romantic -- you’d say sappy -- story. I remember the scenario of your origin you’ll suggest when you’re twelve.

“The only reason you had me was so you could get a maid you wouldn’t have to pay,” you’ll say bitterly, dragging the vacuum cleaner out of the closet.

“That’s right,” I’ll say. “Thirteen years ago I knew the carpets would need vacuuming around now, and having a baby seemed to be the cheapest and easiest way to get the job done. Now kindly get on with it.”

“If you weren’t my mother, this would be illegal,” you’ll say, seething as you unwind the power cord and plug it into the wall outlet.

That will be the house on Belmont street. I’ll live to see strangers occupy both houses, the one you’re conceived in and the one you grow up in. Your dad and I will sell the first a couple years after your arrival. I’ll sell the second shortly after your departure. By then Nelson and I will have moved into our farmhouse, and your dad will be living with what’s her name.

I know how this story ends; I think about it a lot I also think a lot about how it began, just a few years ago, when ships appeared in orbit and artifacts appeared in meadows. The government said next to nothing about them, while the tabloids said every possible thing. And then I got a phone call. A request for a meeting.

I spotted them waiting in the hallway, outside my office. They made an odd couple; one wore a military uniform and a crew cut, and carried an aluminum briefcase. He seemed to be assessing his surroundings with a critical eye. The other one was easily identifiable as an academic: full beard and mustache, wearing corduroy. He was browsing through the overlapping sheets stapled to a bulletin board nearby.

Totals:

523 words

190 - characterization: 36%

36 - Plot/story conflict: 7%

42- Description : 8%

208 - gold standard: 40%

37 - unspecified: 7%

Voice: Alternating 2nd person present/future with “subjective past” mixed in, based on the scene.

Tropes in the first 500 words: Aliens & artifacts

Number of words until a Sci-fi trope is introduced: 419

Please note: this exercise reflects my impression of the work PRIOR TO reading the full story. I’ll not give away the twist, but the ending of the novella puts the beginning in context in such a way that most of the above highlights would be changed to “the gold standard.” This is an important distinction: the beginning must stand on its own out of context. The ending doesn’t matter because the reader, the agent, the editor will never read the ending to put the beginning in context if the beginning doesn’t hold their attention.

Is it over the top to use bold and italics at the same time? Yes. Have I had this fight with multiple undergraduate students over the years? Also yes. I’ll say now what I couldn’t say in the classroom: No one does — or ever will — give one single solitary shit about your ending if they don’t buy into your beginning.

This is why exchanging your work with a critique partner is the crux of this exercise. You, the writer, know your story. You know its brilliance and all it’s supposed to accomplish. But your critique partner doesn’t. If you find yourself explaining why you made the highlights you did, especially if those highlights are “the gold standard” or rely on reading the story’s ending, then stop. Take a breath. Try to listen. Maybe exchange your work with a different critique partner. If both partners come back with similar highlights, you’ll know that there are changes to be made.

Now, back to Ted:

So, what does this exercise tell us about Stories of Your Life? For one, Ted Chiang does a lot of things at once. When I first read the book, I noted the tense shifts from present to future at points and viewed that as foreshadowing (which is exactly what he intended). Most often, he combines character & description or character & plot foreshadowing. That’s why I picked this piece for the first post. Always, we should strive to have our prose deliver multiple facets of our story concurrently.

Additionally, though this is a highly descriptive passage, the amount of straight up description is relatively low, and, especially at the end when the government shows up, the description is combined with pushing the plot forward, or character revelation early in the manuscript.

Finally, I always like to track when the first genre trope shows up in the story. Here, Ted takes nearly the full 500 words to mention that the story is Sci-Fi. Usually, I’d tell my students to revise their work to telegraph the genre earlier — in the first paragraph or first few sentences. But here, the beginning is so brilliant and full of character revelation — not to mention simply beautiful prose — that he gets away with it. The story works.

As we go through other first pages over the next few weeks, you may notice that no two stories look exactly alike — and that’s okay. Quite frankly, that’s sort of the point of stories. If your beginning doesn’t look like Ted’s, it doesn’t mean it’s bad or unpublishable. It just means that you’re not Ted Chiang — and that’s good news, because Ted Chiang is already Ted Chiang. The world doesn’t need more than one. It needs your story too. Hopefully, you can take something away from this exercise that helps you in your revisions.

Good luck, and happy writing.

Interested in hiring me as a developmental editor? Email archetypistpodcast@gmail.com for more information and a free first page evaluation and consultation.

Like this post? Check out the full Archetypist podcast episode below about Ted Chiang’s Stories of Your Life.