Welcome to the third week of the “Beginnings are Hard” series. In these posts, I analyze the first 500 words (or so) of award-winning or bestselling novels to see how they work.

For an in-depth introduction, an explanation of my methodology, and a look at Ted Chiang’s Story of Your Life, click here.

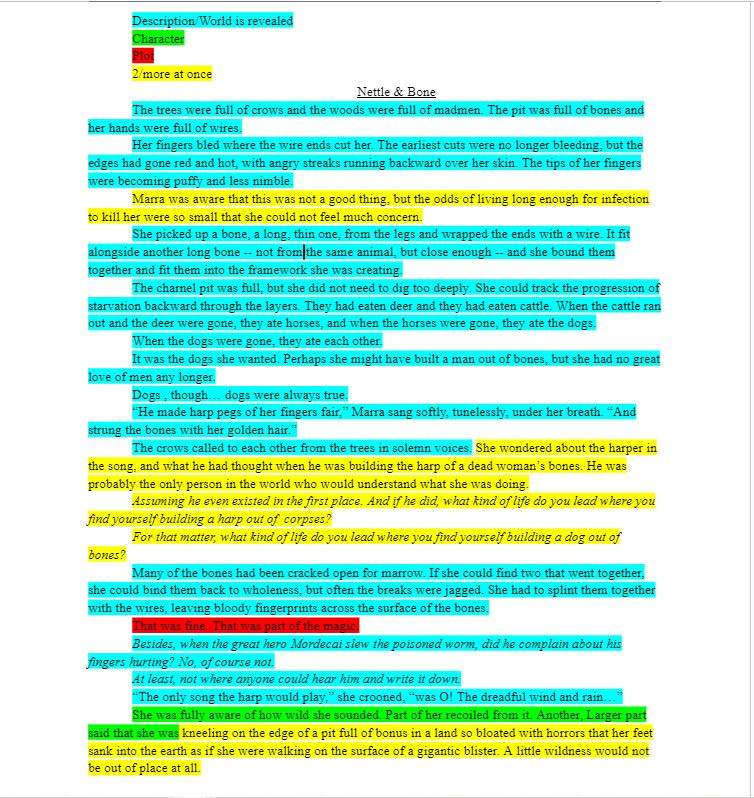

I first learned about this diagnostic at a workshop put on by Kurestin Armada, a literary agent. This simple highlighting system can be used to analyze what work your words are doing, and what areas of your beginning may be lacking. Not every sentence of your manuscript will be highlighted, but if there’s more than 10-15% of un-highlighted words, there’s probably work to be done.

The exercise:

Take the first 2 pages (500 words) of your novel and print them out. Make two copies. Then get 4 different colored highlighters and mark the following:

Character is revealed in Green

Plot/Conflict is revealed in Red

Setting/Description in Blue

Two or more of the previous 3 happening at once: Gold (or the gold standard).

This exercise is meant to be done by an uninformed reader, as if your manuscript just came across an editor’s desk that wouldn’t know you from Adam. That’s why, when you’re analyzing your own work, it’s important to switch with a critique partner or two. You already know how your story ends. They don’t. If there are discrepancies between your highlighter colors, that tells you that you’re relying on the rest of your story to carry your beginning. I find that, as I’ve gone back after reading these novels a second time, I’m more liberal with my yellow highlighter because I can see the shape of the story reflected in the first pages.

The un-highlighted excerpt is pasted below, followed be a screengrab of my highlighting system. See you on the other side!

Nettle & Bone

The trees were full of crows and the woods were full of madmen. The pit was full of bones and her hands were full of wires.

Her fingers bled where the wire ends cut her. The earliest cuts were no longer bleeding, but the edges had gone red and hot, with angry streaks running backward over her skin. The tips of her fingers were becoming puffy and less nimble.

Marra was aware that this was not a good thing, but the odds of living long enough for infection to kill her were so small that she could not feel much concern.

She picked up a bone, a long, thin one, from the legs and wrapped the ends with a wire. It fit alongside another long bone -- not from the same animal, but close enough -- and she bound them together and fit them into the framework she was creating.

The charnel pit was full, but she did not need to dig too deeply. She could track the progression of starvation backward through the layers. They had eaten deer and they had eaten cattle. When the cattle ran out and the deer were gone, they ate horses, and when the horses were gone, they ate the dogs.

When the dogs were gone, they ate each other.

It was the dogs she wanted. Perhaps she might have built a man out of bones, but she had no great love of men any longer.

Dogs , though… dogs were always true.

“He made harp pegs of her fingers fair,” Marra sang softly, tunelessly, under her breath. “And strung the bones with her golden hair.”

The crows called to each other from the trees in solemn voices. She wondered about the harper in the song, and what he had thought when he was building the harp of a dead woman’s bones. He was probably the only person in the world who would understand what she was doing.

Assuming he even existed in the first place. And if he did, what kind of life do you lead where you find yourself building a harp out of corpses?

For that matter, what kind of life do you lead where you find yourself building a dog out of bones?

Many of the bones had been cracked open for marrow. If she could find two that went together, she could bind them back to wholeness, but often the breaks were jagged. She had to splint them together with the wires, leaving bloody fingerprints across the surface of the bones.

That was fine. That was part of the magic.

Besides, when the great hero Mordecai slew the poisoned worm, did he complain about his fingers hurting? No, of course not.

At least, not where anyone could hear him and write it down.

“The only song the harp would play,” she crooned, “was O! The dreadful wind and rain…”

She was fully aware of how wild she sounded. Part of her recoiled from it. Another, Larger part said that she was kneeling on the edge of a pit full of bonus in a land so bloated with horrors that her feet sank into the earth as if she were walking on the surface of a gigantic blister. A little wildness would not be out of place at all.

Notes

This book begins with description and immediately starts to build atmospherics -- those aspects of the setting that create mood -- and sometimes by extension, theme. Trees, crows, woods, madmen, pits, bones, blood, wire. The reader is immediately introduced to the story with death imagery and the setting of the archetypal dark woods full of unknown horrors. From a genre perspective, we see the beginnings of a magic system -- one that has a real cost to the protagonist.

Additionally, we start with the protagonist in motion. She’s building something in a dangerous place out of bones and wire and blood. Next, we move into character traits and stakes. Death is on the line, but the main character doesn’t care. She’s at her wit’s end, taking drastic measures.

The blue section that starts with “the charnel pit.” Is incredible, in my opinion. I almost marked it yellow, but had to mark it blue because it really only does one thing by our metrics: reveals the world through description. But how the world is revealed is really cool here. She’s giving an oral history of these people, whoever these bones belong to, based around what they ate. She’s building the world, building atmospherics through folklore. She’s both revealing the physical aspects of the scene while simultaneously giving context to the larger world in which this story operates.

The second “gold standard” section starts with “She wondered about the harper…” Here, Kingfisher is relating the folklore she’s built with this song to the character’s internal psyche/emotional center. She’s engaging with the history of the world that she’s created while also revealing a truth about the character.

Also, can I just say, opening a book by having your character build a dog out of bones is just great writing.

I marked the “that was fine” stand-alone line paragraph as plot, because it promises at a future action/payoff to a character action that’s being done in the present.

I marked “she was fully aware of how wild…” as character because it’s straight internal monologue, and that passage transitions into “gold standard” because that internal monologue is re-grounded in the scene through description.

The Numbers:

546 words

Description/World: 347/546 = 64%

Character: 22/54 = 4%

Plot: 9/546 = 0.01%

Gold Standard: 168/546 = 31%

Summary

This is a description-heavy story told through a close, reflective P.O.V. The author relies on description to build atmospherics and hook the reader. The mood is ominous and gritty. This feels like a dangerous place where the character is exposed and in motion. She’s attempting a task that apparently has some stakes, though the reader is not told why she’s building the bonedog or why things are the way they are in the larger world.

The character is then introduced through the lore of the world. Fragments of songs, that also build atmospherics, and then quick, pointed thoughts. The author does not allow the character to go off on a tangent and explain herself, but rather trusts her prose to carry the reader to where they want to go. This is a good lesson.

The first page of this book hooked me and I was in for the entire ride.