Welcome to the second week of the “Beginnings are Hard” series. In these posts, I analyze the first 500 words (or so) of award-winning or bestselling novels to see how they work.

For an in-depth introduction, an explanation of my methodology, and a look at Ted Chiang’s Story of Your Life, check out last week’s post.

The Crash Course Intro:

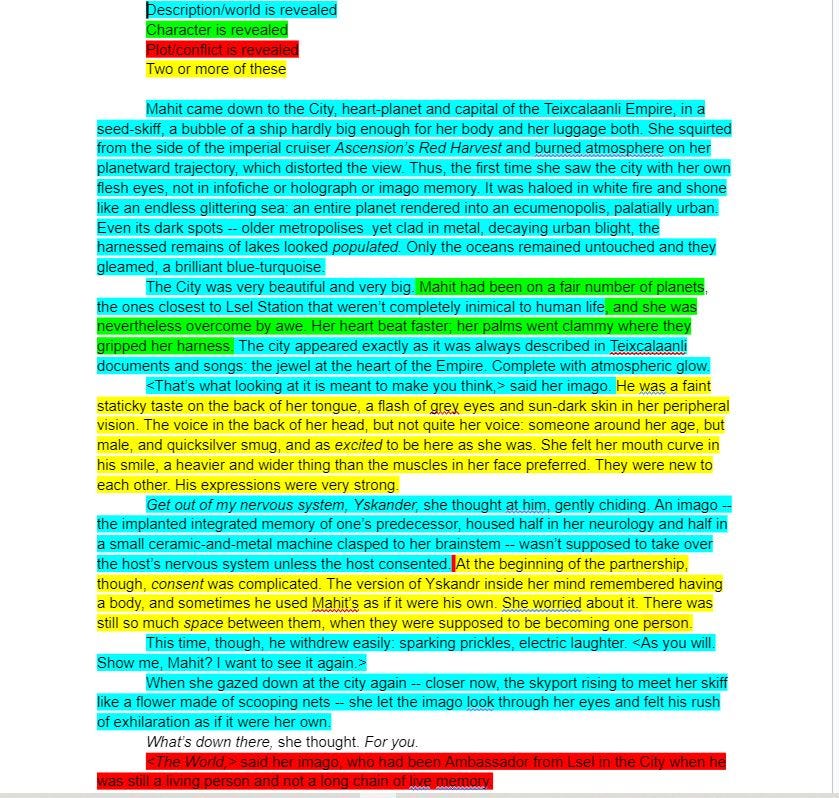

I first learned about this diagnostic at a workshop put on by Kurestin Armada, a literary agent. This simple highlighting system can be used to analyze what work your words are doing, and what areas of your beginning may be lacking. Not every sentence of your manuscript will be highlighted, but if there’s more than 10-15% of un-highlighted words, there’s probably work to be done.

The exercise:

Take the first 2 pages (500 words) of your novel and print them out. Make two copies. Then get 4 different colored highlighters and mark the following:

Character is revealed in Green

Plot/Conflict is revealed in Red

Setting/Description in Blue

Two or more of the previous 3 happening at once: Gold (or the gold standard).

This exercise is meant to be done by an uninformed reader, as if your manuscript just came across an editor’s desk that wouldn’t know you from Adam. That’s why, when you’re analyzing your own work, it’s important to switch with a critique partner or two. You already know how your story ends. They don’t. If there are discrepancies between your highlighter colors, that tells you that you’re relying on the rest of your story to carry your beginning. I find that, as I’ve gone back after reading these novels a second time, I’m more liberal with my yellow highlighter because I can see the shape of the story reflected in the first pages.

The un-highlighted excerpt is pasted below, followed be a screengrab of my highlighting system. See you on the other side!

Mahit came down to the City, heart-planet and capital of the Teixcalaanli Empire, in a seed-skiff, a bubble of a ship hardly big enough for her body and her luggage both. She squirted from the side of the imperial cruiser Ascension’s Red Harvest and burned atmosphere on her planetward trajectory, which distorted the view. Thus, the first time she saw the city with her own flesh eyes, not in infofiche or holograph or imago memory. It was haloed in white fire and shone like an endless glittering sea: an entire planet rendered into an ecumenopolis, palatially urban. Even its dark spots -- older metropolises yet clad in metal, decaying urban blight, the harnessed remains of lakes looked populated. Only the oceans remained untouched and they gleamed, a brilliant blue-turquoise.

The City was very beautiful and very big. Mahit had been on a fair number of planets, the ones closest to Lsel Station that weren’t completely inimical to human life, and she was nevertheless overcome by awe. Her heart beat faster; her palms went clammy where they gripped her harness. The city appeared exactly as it was always described in Teixcalaanli documents and songs: the jewel at the heart of the Empire. Complete with atmospheric glow.

<That’s what looking at it is meant to make you think,> said her imago. He was a faint staticky taste on the back of her tongue, a flash of grey eyes and sun-dark skin in her peripheral vision. The voice in the back of her head, but not quite her voice: someone around her age, but male, and quicksilver smug, and as excited to be here as she was. She felt her mouth curve in his smile, a heavier and wider thing than the muscles in her face preferred. They were new to each other. His expressions were very strong.

Get out of my nervous system, Yskander, she thought at him, gently chiding. An imago -- the implanted integrated memory of one’s predecessor, housed half in her neurology and half in a small ceramic-and-metal machine clasped to her brainstem -- wasn’t supposed to take over the host’s nervous system unless the host consented. At the beginning of the partnership, though, consent was complicated. The version of Yskandr inside her mind remembered having a body, and sometimes he used Mahit’s as if it were his own. She worried about it. There was still so much space between them, when they were supposed to be becoming one person.

This time, though, he withdrew easily: sparking prickles, electric laughter. <As you will. Show me, Mahit? I want to see it again.>

When she gazed down at the city again -- closer now, the skyport rising to meet her skiff like a flower made of scooping nets -- she let the imago look through her eyes and felt his rush of exhilaration as if it were her own.

What’s down there, she thought. For you.

<The World,> said her imago, who had been Ambassador from Lsel in the City when he was still a living person and not a long chain of live memory.

510 words

Character only: 29/510 = 6%

Plot only: 29/510 = 6%

World/description only: 306/510 = 60%

Gold standard: 139/510 27%

Narrative

This passage is incredibly description/world heavy, as is expected with a Hugo-award winning sci-fi masterpiece. The premise of this story, “A Stranger Comes to Town,” lends itself well to allowing the author to explain the new world to the reader as the character understands it. This is a story about assimilation, arguably forced assimilation, under an aggressively expanding nation --a cultural center that views themselves as superior to the out group (of which Mahit is a member). It’s not apparent on the first read-through, but the reason why Martine spends so much time describing this city, is because Mahit absolutely LOVES the empire’s culture despite its slow annihilation of the customs of Lsel Station. Mahit is struck with wonder when she comes down into it, and so Martine communicates that wonder to the reader, which, in a way reveals character. On a second readthrough, I’d change the first paragraph to “yellow” because the narrator is showing the protagonist’s enthusiasm by allowing her to linger there.

The first block of “gold standard” text is marked as such because Martine seamlessly dips in and out of characterization and revealing the world. On the second read-through, it’s apparent that she’s also foreshadowing one of the main story conflicts as well regarding the imago technology (intentionally vague to limit spoilers).

The second block is marked as gold for the same reasons, but also because here, all three elements (character, plot, and world) have come together beautifully. This technology is new to Mahit and she’s worried about it. There’s tension between her and her imago around the issue of consent, and there’s discord over how they’re not quite bonding like a traditional imago/ambassador pair would. This creates a masterful meld of world, character, and a potential plot point.

Finally, I’d like to compare this passage with the one from last week:

Story of Your life

523 words

190 - characterization: 36%

36 - Plot/story conflict: 7%

42- Description : 8%

208 - gold standard: 40%

37 - unspecified: 7%

A Memory Called Empire

510 words

Character only: 29/510 = 6%

Plot only: 29/510 = 6%

World/description only: 306/510 = 60%

Gold standard: 139/510 27%

Note that both novels have won awards. Memory won a Hugo. Story won a Nebula and was nominated for a Hugo. It’s also worth noting that both novels fall squarely within the Science Fiction genre but have have allocated their beginnings totally differently.

Next week, we’ll take a look at Recursion by Blake Crouch.

I love A Memory Called Empire. The Aztec-inspired culture of the empire that doesn't try to whitewash the culture, it's appreciation of poetry (even to the point of using in-universe poetry to resolve major plot points!), and the way that we are so taken in with the narrator's infatuation with the culture of the empire despite its glaring issues, all come together to create a science fiction book that feels like something genuinely NEW.

I haven't heard of this approach to highlighting the first 500 words, but it looks like an interesting exercise; I'll have to try it out on my own WIP.