This post is part of Art & Craft, my series that reviews books about writing books.

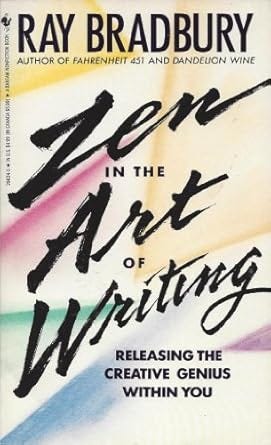

Part memoir, part inspirational reflection, and part craft, Zen in the Art of Writing is a collection of essays that can be read in a sitting. I typically pass over such “collections.” In my opinion, they’re publisher cash grabs, an excuse to produce another book by a Big Name without the Name producing anything new. But the fans always scoop them up—and I must admit I am a fan.

Why I chose this book

Ray Bradbury is one of those rare authors who can write anything and the world will call it literary. Something Wicked This Way Comes is delightful horror, Fahrenheit 451 is classic dystopia, and yet Bradbury is the type of writer whose books get assigned by teachers and even professors. He smashes the perception of the “junk” genre writer, so when I remembered he had a craft book I decided to slip it into this series.

The highlights

I struggled with how to format my summary of takeaways from this book because, since it is a collection of essays, the book itself lacks any such structure. Which is not a criticism. Maybe it’s a refreshing break from screedy chapters on “Plot,” “Character,” and “Prose.”

It’s been a few weeks since my initial readthrough, and this review has been slow in coming because I’ve been heavily focused on fiction (and childminding). While I completed a short story and started drafting my next novel, I found myself reflecting on two questions, both formed by Bradbury’s reflections.

How does my writing compare to other writing… if I should compare at all?

This question is about genre. Probably.

In one of his earlier essays, Bradbury reflects on the impossibility of writing in a vacuum: “The problem for any writer in any field is being circumscribed by what has gone before or what is being printed that very day in books and magazines.” [page 14, essay: “Run Fast, Stand Still…”] Maybe we can initially imagine and even draft freely, but as we revise in preparation for submission, querying, and self publishing, we might wonder which markets, agents, and indie niches would be most suitable for our work. Or, faced with the increasing competition of shrinking market opportunities, we frequently wonder how to revise and reshape our work in the image of these would-be destinations.

In my zen meditation, I ask myself the deeper question. What would my writing be like if I didn’t entertain these questions? I can’t help but be inspired by what has moved me, but is it possible to abandon all but the positive influences on my work?

Bradbury might have us believe that the path to the best stories (i.e. most popular) is a combination of established conventions and broken rules: “We are so used to the dynamic of ‘literary’ as opposed to ‘commercial’ writing that we haven't labeled or considered the Middle Way, the way the creative process that is best for everyone and most conducive to producing stories that are agreeable to snobs and hacks alike.” [pages 128-129, essay: “Zen in the Art of Writing”] Titles like Station Eleven and Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow might present evidence for this idea.

But, to advocate even against myself, not all writers care about producing something popular. That would be great, but there’s a reason we don't all write bodice-rippers. And sometimes we want to produce something that belongs solidly within a certain genre. But I doubt genre is often the source of inspiration. Even “plotters” who write based on very structured outlines will boundlessly brainstorming at the start.1 Genre is often where we land when we’re finished, how our work must inevitably be marketed. This is why many writers find themselves backing into genre, or outright struggling to identify with one.

I don’t think I have a solid conclusion for this reflection, but I’m in love with the exploration. The initial idea behind The Archetypist was a platform for Jacob and I to dissect the conventions and tropes of genres and their subgenres. We only dove into science fiction in our podcast series, but I plan to explore this idea further in future posts (and maybe podcasts, if my kids master the art of silence).

What does my writing have to do with who I am?

This question is about authenticity, which Bradbury emphasizes over and over: “Do not, for the vanity of intellectual publications, turn away from what you are—the material within you which makes you individual and therefore indispensable to others.” [page 42, essay: “How to Feed and Keep a Muse”]

I recently wrote a short story about a very specific type of abuse I have experienced. It was not easy to write. The piece was short, but it took quite a long time. And it might be the most impressive thing I’ve produced.

I don’t think I would have written that story, or accomplished the polished, emotive outcome, without reading this collection of essays. If you’re struggling with ideas, try this for a prompt: What makes you uncomfortable, or what do you deeply hate? In the other direction, what makes you the most ecstatic and enthused? A strong story idea is the overlap between one of those sensations and an experience you believe most people don’t quite understand. And so you write the story.

What do you mean, “literary”?

I’ll crown this section with one more quote for anyone who’s still fueling the online content mill with diatribe about whether SFF is literature:

“The children sensed, if they could not speak, that the entire history of mankind is problem solving, or science fiction, swallowing ideas, digesting them, and excreting formulas for survival. You can't have one without the other. No fantasy, no reality… no impossible dreams. No possible solutions. [page 96, essay: “On the Shoulders of Giants”]

The cringe

I have only two critiques of Zen in the Art of Writing. First, from a pure “looking for craft advice” perspective, the book becomes repetitive and irrelevantly autobiographical. If I looked at this through my fan lens alone, I might love his accounts of the sources of inspiration for his plethora of short stories.

Secondly, there is very little in the book that is technical. This might be related to Bradbury’s literary approach—writing is more about the experience, the sentiment, than the technique. In the preface to this collection, he insists: “You must stay drunk on writing. So reality cannot destroy you.” [preface] We can hardly execute a technique or adhere to the (however informal, unenforceable) rules of writing if we remain dutifully, artfully intoxicated.

Star-ratings

How useful is this craft book?

2 out of 3 stars - ★★☆

How humble is this craft book?

2 out of 3 stars - ★★☆

How concise is this craft book?

3 out of 3 stars - ★★★

Blessed are they who read through this ramble. I’ll close with a (depressing) reflection on how I’ve been feeling about SFF and the industry recently… I wish I could just say “Ray Bradbury was so great, I love being a fan, I’m so happy I decided to add his book to this series, he contributed so much to the community.” But I can’t. Because I don’t know if or how he contributed to the toxic, manipulative culture that seems pervasive among writers. The best I can say is I hope he never did anything unforgivable, and if you’re an author, especially someone new to this, for the love of God take care of yourself and your friends. Stay safe, stay connected.

Aside: rather excited for my re-read and review of Shawn Coyne’s Story Grid

I haven't read this and don't plan to after reading your review. Thanks for sharing. =)