Archetypist Discovery-Outline Method for Writing a Novel

Writer's block HATES him for this ONE WEIRD TRICK!!!!111one!!!!11!!!!

You've heard the question: are you a pantser or a plotter? A builder or a gardener? A discovery writer or an outliner?

These binary terms for how writers prefer to work have become less descriptions of our processes and more “personal creeds” that are extolled throughout writing forums, podcasts, and craft books. I was talking to a writer friend recently and they shared that they wished they were an “outliner,” but alas, they were a “pantser” and therefore doomed to be stuck in a cycle of perpetual rewriting as they made the story up as they went along.

Likewise, I’ve talked to strictly “plotters” who have expressed admiration for the “pantsers” who seemingly spin their first draft out of thin air with nothing guiding them but their heart.

However, this is a false paradigm. Everything is discovery writing at its inception. The discovery/outline terms simply describe when and how the writer’s brain prefers to get dopamine. To be a bit reductionist, discovery writers feel they are doing their best work when the plot/structure/characters of the first draft fall into place during the process of formally writing the first draft. For outliners, they feel they are doing their best work when they are executing a pre-made plan or outline and turning bullet points into full scenes.

I was recently describing my system for drafting novels and someone said to me: “Oh, you’re an outliner then?” This brought me up short because I had considered myself a discovery writer who knows how to outline effectively.

Let me tell you a story.

It’s 2019. I had just come off a year of writing only short stories. I’d graduated from Seton Hill in January of 2017 with an epic fantasy novel that needed a lot of revisions. In fact, it probably needed a full re-write to be the book that I wanted it to be. This had been my first novel that I’d actually finished, and aside from a mind-map collapsing wave exercise, I’d discovery written the entire thing. I ran into a lot of issues and roadblocks, essentially writing myself into corners and then going back and having to delete large portions of the book in order for it to make sense.

Throughout most of 2017, I was working on a SF novel. This time, I’d outlined it. I wrote out a chapter by chapter bulleted list of things that were supposed to happen and I was writing from that outline. Only, I was running into the same problems AND now I wasn’t having fun writing it because I wasn’t really able to “discover” the story as I went along, so I abandoned the project at 90,000 words and the halfway point in my outline. (NOTE: it feels insane to type “I was only halfway done at 90k” but we’ll leave the mistakes of inexperience in the past.

As I said, in 2018 I spent the year writing short stories just to be able to say I finished some things. Some of them even got published on small presses, which was really cool and a huge confidence boost.

In 2019, I felt like it was time to attempt a novel again. I didn’t really become a writer to write short stories. I wanted to see my book on the shelf in Barnes & Noble or Books-a-Million or [insert favorite bookstore here].

I also didn’t want to fall into the same traps that had plagued my writing process before: jumping into a project with an untested premise, only to reach the midpoint of the novel and realize I had no idea where the story was going or that my outline was fundamentally flawed because I skated over an issue or that the outlined story no longer made sense with the characters decision making on the page. So, I decided to design a system of planning a novel using the best of both methods of outlining.

This method consists of discovery writing through summary and using what you’ve discovered to generate an outline, and then using freewriting to discover the atmospherics of the scene/character, etc.

This method also involves writing a lot by hand. You don’t necessarily have to, but I found it to be much more organic and, ironically, more productive. Below, I’ll take you through the materials needed, then some basic definitions of terms so we’re all on the same page. Finally, I’ll share the “Archetypist Discovery-Outline Method.”

Materials:

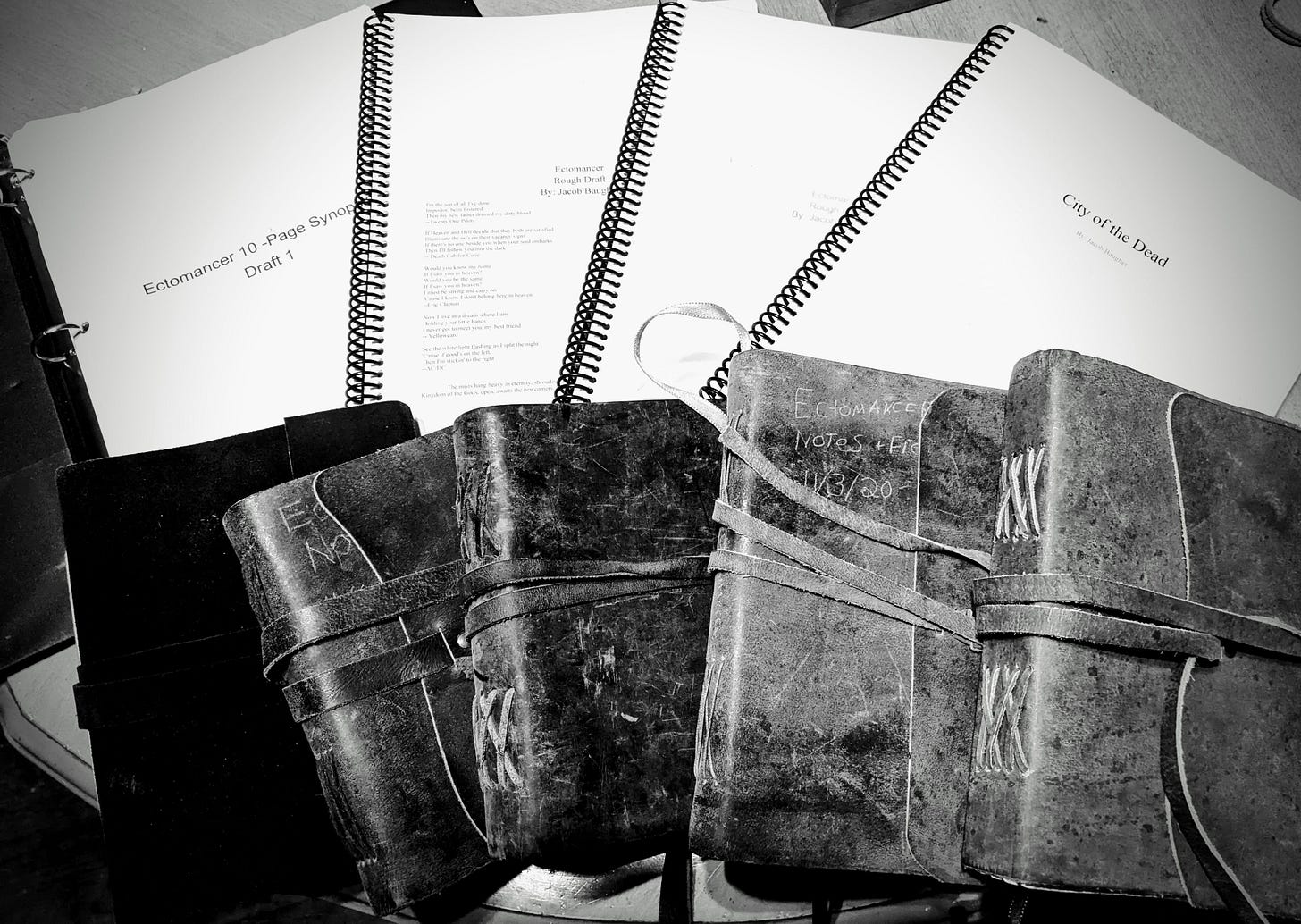

Notebook of choice. I like this leather-bound, unlined one. I’ve ordered that specific notebook 7 different times because it’s cheap, quality, and unlined.

Pen/Pencil of choice. For freewriting I like 1.0mm G2 “10” pens or 1.6mm Zebra pens

If you like the marker feel, Tombow has great felt-tipped pens also

non-bleed felt markers (one color per P.O.V. in your novel

Sticky tack (to hang the paper on the wall safely)

Legal pad

Computer

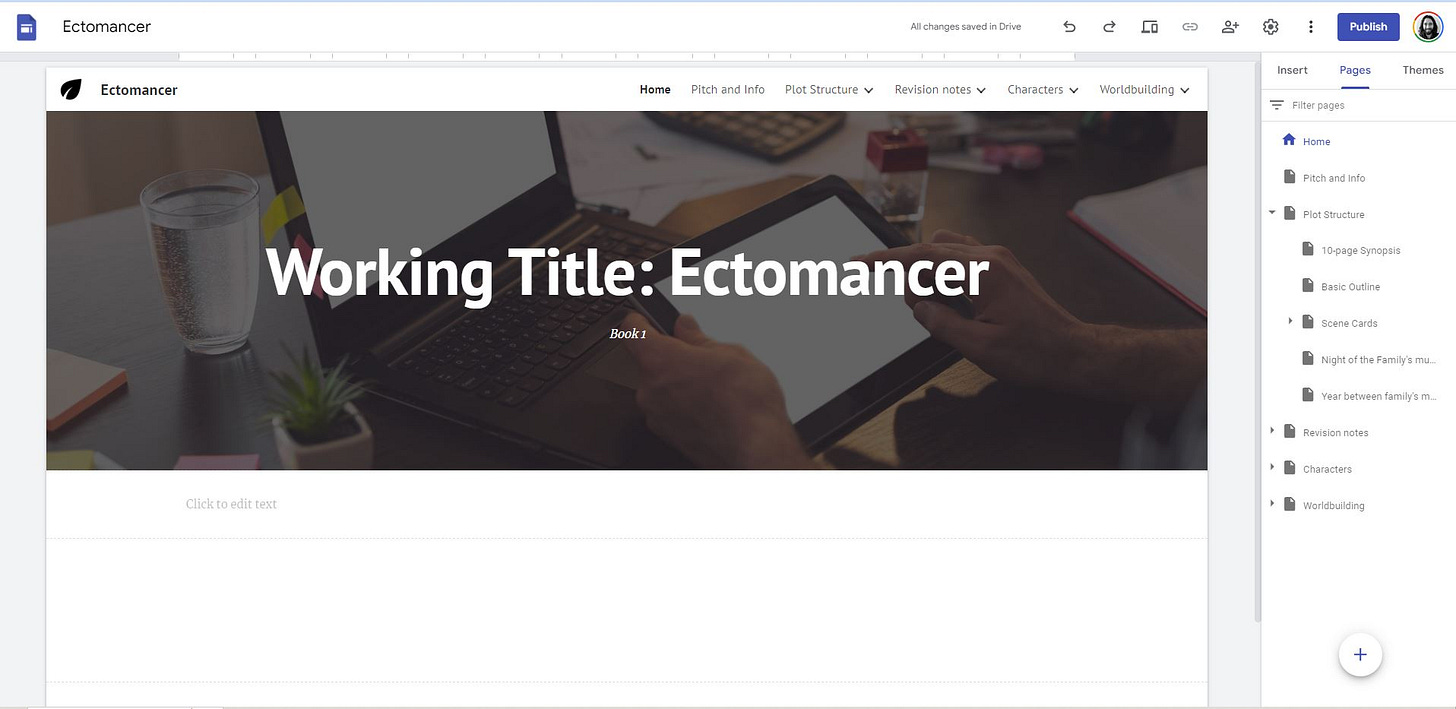

Wiki Software (google sites will do just fine)

Definitions

Freewriting:

The act of setting a timer, putting pen to paper, and writing until the timer goes off, stream of consciousness, EVEN IF you’re not explicitly writing about your story. Freewriting is FREE. We certainly have a goal in mind, but if you want to write “this is stupid. I don’t know what to write about” until your brain gets bored, that’s a totally acceptable use of the exercise. The purpose of freewriting is two-fold. The first objective is, of course, to progress your project, but the secondary objective is to get your body and mind used to writing as close to “on demand” as you can and building up the mental/emotional stamina to write for an extended period. Oftentimes my own freewrites start like journal entries. “I really don’t want to do this. I have a thousand other things to do. This feels stupid. I have no ideas.”

These are important words to write for me, because it gets them out of my head and onto the page. Simply by writing them, I acknowledge that I feel this way and allow myself to move on to the actual meat of writing.

The collapsing wave exercise:

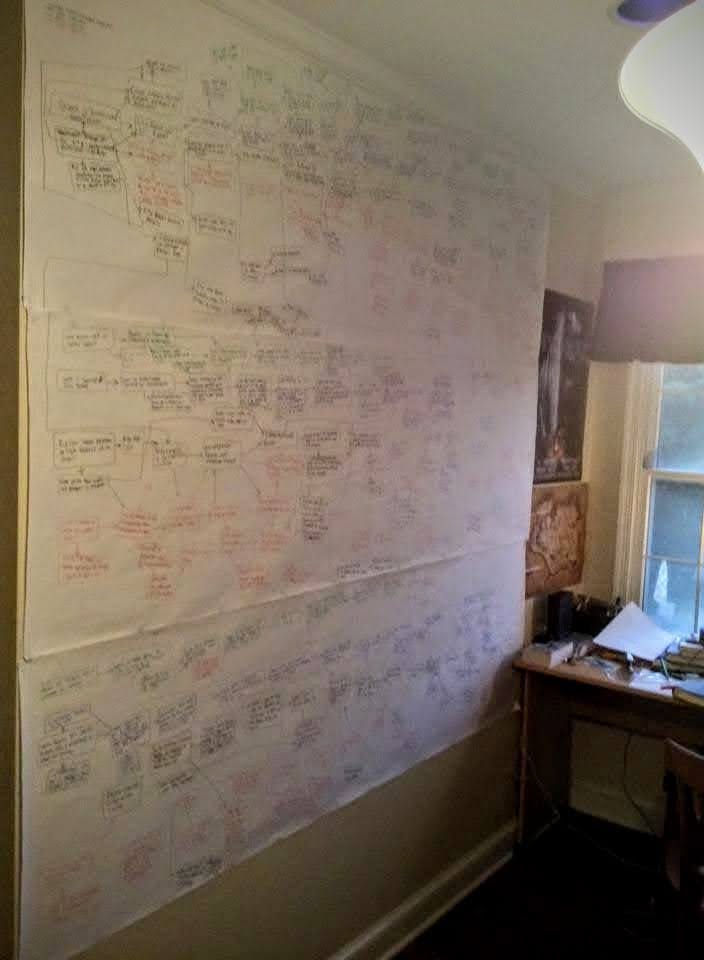

This is an outlining/freewriting tool & a form of mind mapping, where the author writes THE INCITING INCIDENT in a box, and draws a line labeled “Resulting in” to a number of other boxes. An important distinction: the line must be representative of a cause/effect. If you find yourself using the line as the words “and then,” the story will not work.

As your story progresses through the wave, you’ll find the web growing wider and wider. Once you reach the climax, your job is to condense those multitude of boxes into one single box as quickly as possible for an effective climax.

Example:

The main character gets bitten by a zombie [and then] the group goes to the abandoned train station to rest.

The main character gets bitten by a zombie [resulting in] the group abandoning their plans to go to the train station and instead they head to the abandoned CVS for antibiotics.

“But Jacob, that’s ridiculous!” you say, “Of COURSE the group would go to the CVS.”

Maybe, maybe not. It depends on what kind of story you’re trying to tell. The point is that, by following the [RESULTING IN] rule, the writer is forced to stick with the consequences of the scene. By sticking with this rule, the writer holds themselves accountable to the choices they’ve already made in the narrative. If you really, really want to go to the train station and not the CVS, the internal logic of your story must support the decision, and there must be consequences for doing so.

It’s important to note that you’re mapping out possible futures/plotlines here. Not everything in the collapsing wave can or should be in your book. It’s an exercise that helps the writer imagine all possible outcomes to every incident in your story. Some of it will sound “bad” or trite. But it’s important to write out the trite ideas too. Once they’re on the page, they make room for other, more dynamic ideas that may change the trajectory of your book.

Credit where credit is due: I first learned about this tool from Timons Esaias at Seton Hill University.

The Deep Systems Doc

The “book bible” that contains your character names, setting details, plot, synopsis, rules for the magic system, photos of real-world locations in your story, and anything else that could be helpful.

This is a “for your eyes only” document and should contain anything that you potentially think would be worth including in the story AND any research you’ve done on your book, available for quick reference.

The Archetypist Discovery-Outline Method

Brainstorming/Draft 0

Part 1: Define what type of story you’re going to tell. Pick the genre. If there’s a specific plot structure that you want to include, like hardboiled detective or heist or enemies to lovers romance, choose that now. Begin reading a few books in your genre for your pre-work phase if you haven’t already.

Part 2: Know your work & yourself. Freewrite on that structure & genre. Why do you want to write the story that you chose? What’s important for you in that space? Why did you pick that genre. If you’re writing fantasy, try out different magic systems for your story and begin worldbuilding as well. Begin trying out different characters. For my current novel, my character came to me very quickly, nearly fully-formed. That doesn’t always happen, and that’s ok. Freewrite about whose voice can best carry your specific story.

Note: many fantasy novels these days drop 3-5 elements in the first act of the novel that seem innocuous but become very useful/relevant in the climax. Try to find a few here, during this phase.

For me, this phase of the process took up maybe 1/2 of a handwritten journal. And this really should be a journal exercise, stream of consciousness. Do not hold yourself back. If characters, themes, or scenes jump out at you, indulge them. Write them through to their natural completion. Additionally, freewrite on the final image of your story, or how you want it to end. You don’t have to have a specific scene in mind, but more of a general feeling.

ex: “I think this story is one about overcoming darkness. About the main character standing up against impossible odds because it is the right thing to do and triumphing in the end. But I also think this story is about sacrifice, and how sometimes you have to give something valuable up to triumph over evil….”

I cannot stress enough that this is important work to do for your novel. It will focus you, help you hold in your mind the theme & tone of your story, and inform the rest of your book. Really take your time here. A few weeks or so, of writing every day about your project. And do make sure it’s about your project and not an actual draft of your project. These journals may be useful to look back on before you start pitching your book to agents as well.

Use the information gleaned in this phase to begin building your deep systems doc wiki page (I used google sites).

Another note: during this process, it may be very hard to hold off starting to write your actual draft. That feeling is totally normal. Indulge yourself a bit. Summarize your idea and maybe write a few paragraphs of the scene in mind, but don’t dive in headfirst yet. We’re not ready.

Part 3: Decide on your inciting incident and do the collapsing wave exercise until the book reaches its natural end. Decide which branches of the wave make sense to follow and eliminate the plot points that feel obvious, trite, or just don’t fit with how the story is shaping up. Make sure the story’s internal logic is sound.

Part 4: Write a loose outline of scenes using the information gleaned from the collapsing wave exercise. If there are parts that are not working/don’t seem to fit with the narrative that’s shaping up, or just seems “off,” go ahead and freewrite on those problems.

Part 5: Grab that legal note pad from your “materials” list and revise that outline down until the main idea of each scene fits on a single line of the notebook

Part 6: Create scene cards/Write your Draft 0. You can use physical scene cards, or I used my google site wiki so I could have infinite space. Each scene card/page should have the 1-line descriptor from your legal pad at the top of the page, so you keep the scene’s objective in mind. Then, I freewrite on the scene. I decide on the setting, the time of day, which characters are involved, how they’re feeling, and what each one wants out of the scene. Then I crack open my journal and hand-write a “draft 0”

Usually for me this mixes in summary writing "they go here and do this and feel this way" with actual scene excerpts/seeds in “formal style.”

"The characters go to the ancient temple to look for the missing ring. It's cold inside, despite the hot desert sun raging in the sky. The scents of dust and still air and something long-dead rotting in some forgotten sarcophagus oppress the atrium, a stark contrast to how she remembered the place in her youth: incense and baking bread. Perfumed bodies and clean sweat. That tell-tale smell of holy water that no one can ever quite describe, but knew innately.

"Well, this sucks," Leon said.

They search the rest of the temple and find the ring in the sanctuary. When he picks it up, a ghost materializes and..."

The point of the 0 draft is to hold the story in your mind by the end of it, and to see how the scenes fit together, and help you diagnose potential problems that may crop up while drafting your "formal” draft 1.

Note: I combined the scene-card/draft 0 step because I find that they happen simultaneously. I tended to start on the scene card, freewrite on the setting, character wants, etc, and the beginning of a scene would come to me. Then, I’d either flow right into writing the scene summary directly into my wiki/deep systems doc, or flip open my journal, handwrite it, and then input the hand-written words into the deep systems doc.

Part 7: Write your 1-page synopsis.

Part 8: Write your 10 page synopsis.

Part 9: Take a 1-week break to let things settle.

Part 10: Re-read your synopsis. Make any revisions. Write your query letter.

The Drafts

Draft 1: The first "formal novel" draft. It consists of looking at all of those scene cards/notes, the entirety of draft 0, and actually writing everything out as it would appear in a book. There is no summary language.

Follow your outline, expand on the scene seeds you wrote in draft 0, etc. Write this draft through to the end. Do not go back and revise aside from maybe reading what you wrote to get yourself back into the story after a break or reviewing at a scene that you weren’t happy with. The point, though, is to get this draft out as fast as possible.

Draft 2: Make it make sense. Here, I print out my story, re-read it with a pen and make notes on it. I fix any plot holes. I may re-write scenes that aren't working.

Draft 3: I do a character revision. Make sure that all characters are behaving correctly/consistently. There aren't any redundant scenes for character development, and they don't just function as cardboard road signs to advance the story

Draft 4: I do a world revision. Make sure that the magic makes sense with the plot, that I don't break the world with the magic, etc. I also check that, if the story takes place in our world, I'm not turning left onto streets I should be turning right onto, that businesses are in the right place, etc.

Draft 5: this is your TIME revision. Make sure we're not writing back to back night scenes, and that the time of day/seasons/weather matches up

Draft 6: This is your voice/poetry revision. HERE is where you get to be "writerly" and make sure you are saying things exactly how you want to say them, etc.

Draft 7: Epigraphs (If needed)

HERE I SEND THE BOOK TO BETA READERS.

Draft 8: Implement/reject beta reader feedback

Draft 9: Grammar/punctuation.

Note that each draft builds off the previous one. Notice I don't spend a bunch of time making things sound pretty UNTIL the story is mostly set in stone because things can change so much. In previous projects, I ran into this issue and was sick of having to cut words I spent a ton of time on.

Also, NOTE: each draft is worked on to completion each time.

That's about it.

It seems like a lot when it's typed out like that but it's really not. I developed this system for my most recent novel and I would have gotten it done in a year if a lot of personal things didn't happen to me. I had draft 0 in 3 months while working part time and being a full-time dad & partner. The pandemic, multiple deaths in the family, additional family trauma, losing my teaching position, and the subsequent job search & depression really ruined my timeline.

The key to this whole system is the brainstorming/Draft 0 section. The beauty of it is that Draft 0 is an easy-lift draft that allows you to really get a sense of your story’s shape. It also has the additional benefit of being mostly hand-written in this system, and has scene seeds scattered all throughout the summary language. This act of taking your handwritten notes and transcribing them back into a word processor for draft 1 frees up your creative brain from the pressure of thinking up everything about the scene all at once. You may already have 500-1000 words written in “formal style” for each scene, that helps inform the “summary” language that links those vignettes together.

The Discovery-Outline system also helps outliners flesh out their outlines a bit and test out their story concept before they sit down to write their formal draft one.

I hope this helps. Drop us a comment if you have any questions or if you want to share your own writing process!

A-mazing. Thank you for taking the same to put down your writing method. I have one of those feelings that it's about to change many aspects of how I'm going to tackle big writing projects. This is now a permanent bookmark on my browser, and have sent it off to some friends. (my hand is aching from so much handwriting, but wow it works!!) I'll let you know when I'm published in Barnes and Noble;)

I followed your same journey, but in reverse. I started with a plotted novel and then decided to discovery write the next one, and I'm glad I did. There are strengths and weaknesses to both techniques, and since then I've done my best to double-dip as much as possible.

I'm intrigued by this collapsing wave method (a reference to the physics phenomenon/computer science algorithm, I presume?) I'm curious to see how it would work for a character-driven novel. Those tend to be motivated by changes in emotional state rather than plot events, but I suppose you could map someone's internal journey the same way you map the movements of armies or the stages of a heist. This might be a case where writing Draft 0 first is helpful, since you can get a clearer sense of the protagonist's emotion in each scene, and THEN map out all possible responses.

P.S. I recognized the Skyrim poster in your grad school thesis photo :P